A new social housing scheme in central London for Peabody marks a deliberate move away

from novelty in favour of longevity.

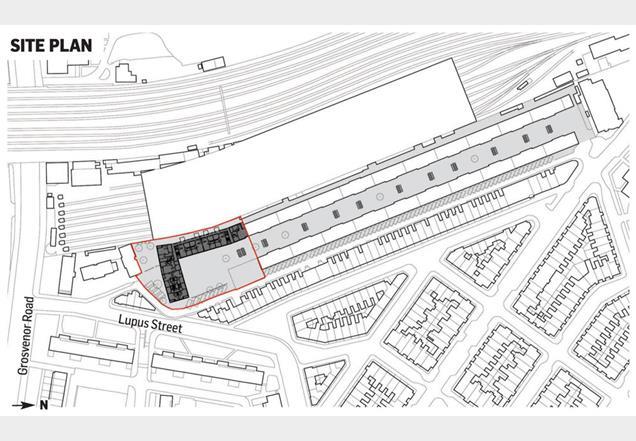

Stretching 280m along the railway sidings south of Victoria station, Pimlico’s Peabody Avenue stands as a linear monument to early social housing. This relentless brick gauntlet, constructed between 1875-78, is perhaps the most austere of Henry Darbishire’s designs for “cheap, cleanly, well drained and healthful dwellings for the poor” built during his time as the Peabody Trust’s architect from 1862-1885 — a period that saw his blueprint used for 14 different sites across London, from Islington to Shadwell.

Squeezed into a narrow, leftover plot between the railway to the west and the well-to-do grid of Thomas Cubitt’s stuccoed terraces to the east, the estate’s 26 blocks were arranged end to end in two parallel rows, like two great trains come adrift from the tracks. Here, the usual Peabody courtyard form was adapted into two opposing tenements, five storeys along the western range, four along the east, separated by an avenue of stately plane trees. Walking between the imposing brick cliff faces today, it is not hard to see why the estate has been used as the film set for a grim Victorian jailhouse.

Bombing in the second world war resulted in the loss of four blocks at the avenue’s southern end, an area that has since accrued the usual bombsite flotsam — a strip of lockups, a ball court, ad hoc parking — and became a magnet for antisocial behavior. Two other blocks were damaged, but remained partially inhabited until the 1990s, when Peabody was finally forced into action.

“One of our residents phoned up and said: There’s a big crack in the wall that I can put my hand in. Is that alright?’” says development director Claire Bennie. The building was evacuated, but a decade of doomed proposals followed. An in-house pastiche scheme was the first to run aground, followed by a larger Feilden Clegg Bradley design, which was vehemently opposed because of its height. As hostility increased, a third attempt was predestined to fail on grounds of its programme: it included rehabilitation homes for former drug users — metres from Pimlico’s parades of prim porticoes and twitching curtains.

Bennie joined the project in 2006, only to be met with a 2,000 signature petition from local residents unconditionally opposing any form of development. It was not going to be an easy ride.

“Communication hadn’t been fantastic,” says Bennie, herself an architect with several years of experience running housing projects. “We really had to go to town on an honest, open and transparent process, with frequent contact with the residents.”

Haworth Tompkins was appointed and, working with facilitator Pat Pegg Jones, spent an intensive year developing designs in close consultation with tenants, fine-tuning proposals according to the specifics of this mixed social and urban fabric. Five years later, against the odds, their £10.4 million, 55-unit scheme now stands at the end of the avenue — and it now seems most residents couldn’t be more delighted.

The L-shaped building extends the western flank of the estate, kinking out slightly to follow the curve of the train line, before turning the corner to form an enclosed end to the avenue. Rights of light issues precluded building along the eastern flank, which has instead been given over to a new landscaped play space, an inviting terrain of red blobs and bridges designed by Jenny Coe.

“We wanted a strong move to enclose the space, but retain the view down the avenue,” says Toby Johnson, director at Haworth Tompkins, as we walk through the move in question — a vast triumphal archway, 5m high and 7m wide, punched through the southern wing of the building to form a bold entrance to the estate — on a scale as grand as Darbishire’s original vision.

“Residents were initially concerned that the covered archway would encourage loitering and rough sleepers,” says Bennie. This fear has proved unfounded — although what could have been a generous urban move, continuing the street beneath the building, has since been hampered by the imposition of metal gates.

To the right, the ground floor is given over to a new resident-run community room, with big glazed doors that open out on to the play area. It already hosts a lively programme of activities, from old people’s craft workshops to yoga and after-school clubs. Next door, looking out over the entranceway, is a new office for the Westminster Wardens — formerly housed at the other end of the estate — the ward’s “dedicated problem-solvers” for environmental issues and anti-social behaviour.

“On principle, Peabody never gates its estates,” she says, explaining that, here, a combination of fast drivers and residents’ wishes led to this exception. “It’s always a matter of experimentation.”

In elevation, the new wing is a sympathetic reworking of Darbishire’s design, only stripped of extraneous — and expensive — Victorian details. The walls, in a more buttery version of the stock brick, exude the same massive quality, with deeply punched windows, and sit on a rusticated plinth of projecting courses, which echoes the coloured banding of the original buildings. Above, a series of lanterns strides along the roofline, mimicking the rhythm of the adjacent chimneys. But the gauged brick arches, dentilled eaves and corbelled sills of 1870s philanthropy, meanwhile, are all lost in translation — substituted for precast concrete lintels and continuous string courses. While it may seem a little Spartan, there is a quality to finish and attention to detail rarely seen in today’s social housing.

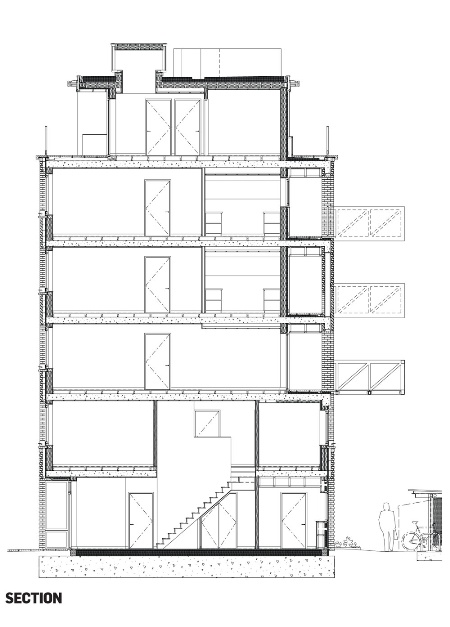

Section

“We spent a long time trying not to make the brickwork too neat,” says Johnson. “Bricklayers are obsessed with the crisp bucket-handle joint, but we wanted this slightly scraggy, smudgy pointing.” The resulting surface has a textured solidity and sense of permanence that is an equal match to its older neighbour.

This is the first completed Peabody project since Bennie took over from Dickon Robinson as the trust’s director of development, and it marks an interesting shift in its philosophy, perhaps in keeping with the chastened times. Under Robinson, Peabody took on a consciously experimental agenda, variously pushing prefabrication and an aesthetic of innovation — from Bedzed’s jaunty eco-bling in Sutton, to Ash Sakula’s sinusoidal plastic cladding at Silvertown, and Munkenbeck & Marshall’s zig-zag copper balconies in Hackney. These projects have been successful in the main, but, as with much that came out of the early noughties, they sometimes favoured novelty over longevity.

“When I sat down with Steve [Tompkins], we agreed there were various modern housing developments that we know and love, but that occasionally have that feeling of flimsiness — thin cladding, metal walls, a certain tinniness,” says Bennie. “We wanted to do something really robust and solid — drawing on the history of Peabody, celebrating our 150th year, but in a modern idiom.”

The trust is currently working on bringing forward 600 more homes across London, including schemes by Pitman Tozer in Bethnal Green, Brady Mallalieu in Whitechapel and AHMM on the Walworth Road, all projects that employ this robust masonry language, but with their own twist — what Bennie describes as “fun with bricks”.

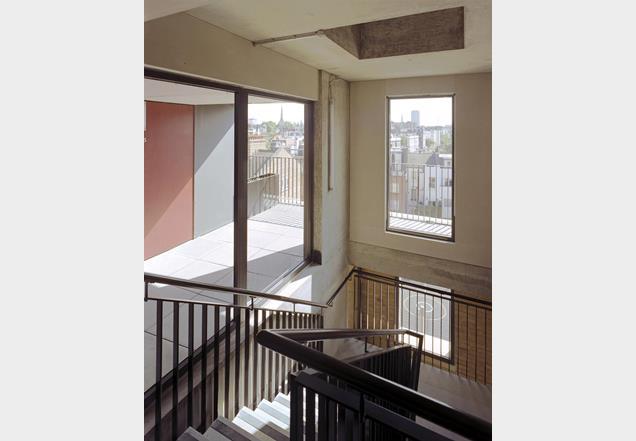

At Peabody Avenue, this sense of restrained, considered fun goes beyond the bricks. The entrances to the circulation cores lead into generous double-height lobbies, and up to open stairwells, complete with treads in York stone and doorways in bright reds, oranges and yellows.

“In every move we’ve aimed for a contemporary reinterpretation of Peabody values,” says Johnson. “Elegant, but utilitarian at the same time.” Flooded with natural light, these cores are in fact a far cry from the gloomy stairwells of the Victorian blocks next door.

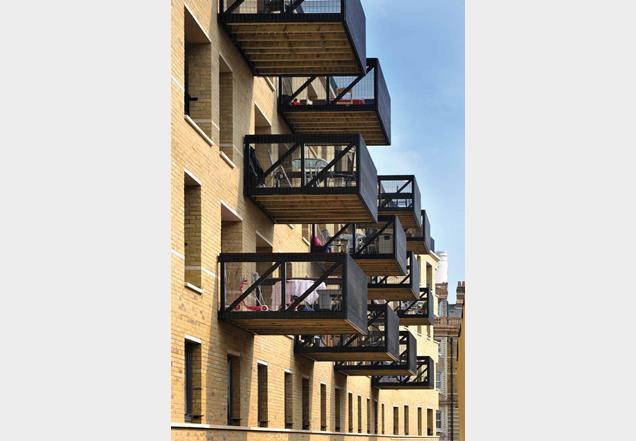

Circulation has been deftly handled throughout, with every unit’s double aspect preserved by running access galleries along the western facade. Here, generous balconies cantilever 2.5m out towards the railway, with expansive views across the river and to Battersea power station beyond. Bennie admits many were sceptical about the placement of private balconies across a public deck, and it is not ideal, but they are already being well used, home to lively collections of tables, barbecues and jungles of pot plants.

Jane d’Angelo, a wheelchair-bound tenant who has lived at Peabody Avenue since 1973 — and whose grandparents lived in one of the first Peabody developments at Old Pye Street — can barely believe her

luck.

Peabody usually has to include a proportion of private units for sale to subsidise the social rented accommodation. But here, Westminster topped up the funding to allow 37 rented units and 18 shared-ownership. The tenure is mixed, with family maisonettes occupying the ground and first floors, with equal numbers of two and three bed units above, while the top level is reserved for accessible units reached by lifts — a rare move for a typology so often confined to the dingy ground floor.

“Before, I had no view at all — it was the back of flats and a pub,” she says, sitting out on her roof terrace, bathed in sunshine, looking out over the river. “Now, even when I can’t get out, I can still sit outside and have views in both directions.”

She admits to expressing horror at the sight of the open-plan kitchen and living room arrangement when she first moved in, but has since come to love it.

Another resident, Maria Effanga, agrees: “I think the way that a property is configured can impact greatly on how well you get on together as a family,” she says, explaining how she enjoys cooking and speaking to her children in the living room at the same time. “We’re sitting together more now, which is something we didn’t do where we were before.”

As with all Peabody infill projects, the new building was first offered to older residents on the estate, encouraging single tenants to downsize from three-bed properties to two-bed units, freeing up family accommodation. This also ensured a level of social continuity — 16 of the 37 units are now occupied by tenants who know the estate, avoiding problems often encountered when an entirely new community is airlifted in.

Throughout the building, high thermal insulation (with u-values of less than 0.15 W/m2k) and low air permeability greatly reduce the demand for heating — the scheme achieving Code for Sustainable Homes level 3.

It is perhaps remarkable that, 135 years after the completion of Darbishire’s Peabody Avenue, this new extension should seem remarkable at all. It is an indictment of today’s developer-built housing that robust, thoughtfully designed homes for affordable rent should be something so extraordinary. Here, Haworth Tompkins has achieved a model prototype that bodes well for the forthcoming wave of new Peabody schemes, showing how it is possible to forget the flimsy paneling and have fun with bricks.

Images bdonline.com

I would like to say that this blog really convinced me to do it! Thanks, very good post

ReplyDeleteHouse Extension in Pimlico

I wanted to thank you for this excellent read!! I definitely loved every little bit of it. I have you bookmarked your site to check out the new stuff you post

ReplyDeletehttps://www.lcrenovation.co.uk/house-extension-in-pimlico/

House Renovations in Pimlico